And why we use it in the first place.

If you have ever read some game dev notes or seen a tutorial on youtube about making a game, you have read the term Object pooling. You might already know how to write an object pooler yourself, or how to access a Unity/Unreal/Godot library that does it for you.

But why do we even use object pooling in the first place? How does everyone mention it? Why don’t we just instantiate objects directly? I plan to write these notes to help you remember why Object pooling is (in general) better than other alternatives.

What is an object pooler

First of all, an object pooler is a programming pattern. That is a code structure, whose implementation could vary depending on the situation. As such, object poolers could differ from company to company, and from game to game. However, the structure could be mostly summarized in this:

StartGame(){

Foreach (object that will be spawned and destroyed){

ObjectPooler.Store(object.Instantiate());

}

//Code

}

Object(){

//Code for the object.

GetFromPool(){

ObjectPooler.GetFromPool(this);

}

ReturnToPool(){

ObjectPooler.Store(this);

this.Gameobject.SetActive(false);

}

//NEVER DESTROY OR INSTANTIATE THIS OBJECT

}So, in other words, the pattern is to avoid Destroying and Instantiating objects, but rather instantiate them at the start and then put them in and out of the pool.

As this is a pattern, a lot of details can change from implementation to implementation. How do I know how many objects to instantiate at the start? Depends on your game. How do I access the object pooler? It depends on your game. Do I reset the object on the GetFromPool() function? Or does each game objects itself do this? Depends on your game.

I will talk about some of these details later, but I mostly want to focus on the why and not on the how. There are enough references for the how. Impossible not to mention the marvellous chapter of Game Programming Patterns on this.

So now on the whys of this pattern; there are three main ones (most experience programmers may mention more, but I will focus on three!.). That is memory fragmentation, memory accessing speed and data locality.

Memory fragmentation

Similarly, as object pooling, you might have heard this term, but not know exactly what this is. Roughly, this refers to the problem/situation in which the memory of your computer is not continuously allocated, so while you have enough memory to load data you don’t have enough continuous memory to allocate it.

Okay yeah. That was confusing. May have not helped this at all. Let’s try again. An example works better.

Suppose your memory has 4 cells of memory. You want to instantiate two game objects that use 2 cells. You clearly should have enough memory to instantiate the objects. So you go and do GameObject.Instantiate. The first one works fine, but the second one triggers a NotEnoughMemory. WHY?

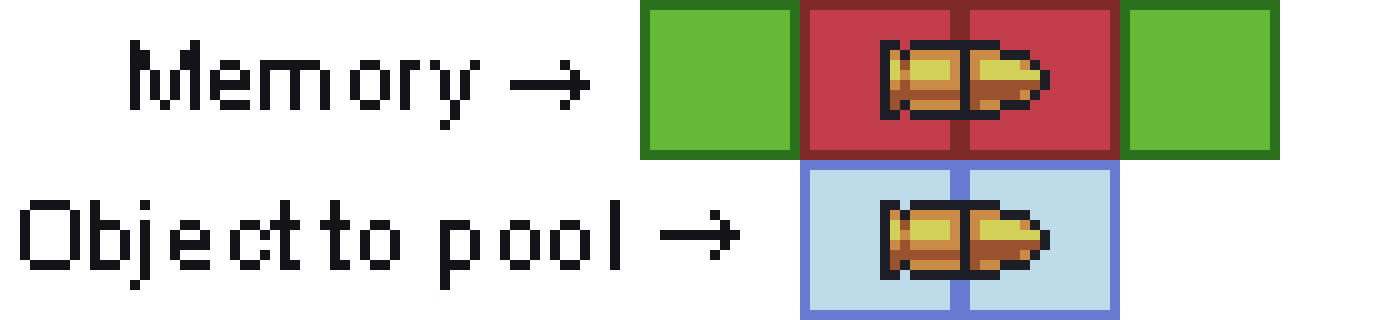

The answer is simple; your computer gives you the memory to instantiate the first objects, but not WHICH memory. So what can happen is the following situation:

An illustration of the situation in memory. You can see poor billy bullet does not fit anywhere without being cut.

See the problem? While the two blocks of memory we want exists, there are not two blocks of memory to put the game object.

The solution to this is to ask for the computer for 4 blocks of memory, and then put the objects in each continuous block. So we ask directly for the pool of 2 objects … so yeah, that is exactly what the object pooler does.

Now, this is not EXACTLY how it works. Modern computers have better memory allocations to avoid that situation (and yes, more memory). But, in reality, the situation I describe can happen if you continuously create and destroy objects during runtime. Using an object pooler will make sure the same blocks of memory are assigned for the same objects, so whatever is instantiated once can be instantiated again. If you are working on a system with limited memory (cellphone for example) this restriction can be game-breaking. The object pooler is the way to go. Now you might be thinking “I only care about PCs with 13571895TB of memory. This does not apply to me”. Well, the next point might be for you.

Memory accessing speed matters

To explain this I will have to explain a bit about how the computer gets data from its system. I will do a terrible job at it. Not because I do not know better, but because for explaining object pooling I do not need to go full technical on this. I will not mention the different types of L-whatever cache. I will not mention most optimizations for data accessing. I will keep this simple. Please forgive me for this. Go read a computer architecture book if you are still offended.

Back to the topic: your computer has main 3 pain parts for keeping memory: A hard drive (or SSD for the lucky ones), RAM and Cache.

The Hard drive is where all the information is recorded. That is where your assets are, where your scripts are stored, and where your build is recorded. However, a hard drive (or even SSD!) is far too slow to access. That is why everything that the computer needs to access its current functions is moved to the RAM.

The RAM is where everything your computer “has opened” is stored. The information of your net explorer right is stored there right now. When you play your game and load a level, everything from that level is stored in the RAM. That is normally what is referred to as “in memory”. However, for working into assets, this is not what your computer uses. It is still too slow. When your PC needs to read and work into something it moves it into the cache.

The Cache is the working desk of your computer. When your computer needs to work on data, it moves it to the cache and works there. When you have a level opened in a game, and some assets it modified this is not done on the RAM. That asset is moved to the Cache, modified, and then stored back again in the RAM.

If you noticed, each level is faster. Which, as you might deduce, is that each level is more expensive. Not in time, mind you, but in money. So each faster level also has less memory, to save cost (and due to other reasons, but again, keeping it simple).

How does this matter for your game? When you use object.Instantiate() (normally) what your engine does it goes to your HD, get the information of your object, and then copies it into RAM. This is INCREDIBLE slow when compared to the alternative of the object pooler; just make the object in the pooler active again. How much faster? Reading from RAM is between 50 to 200 times faster. Imagine your object to instantiate are bullets. And you fire them once each frame. Can you compute how much time you have lost in 60 frames? (You could have to manage the bullets 12,000 times faster in case it is not clear).

That means object pooling is not only a memory managing thing but also a performance thing. Now, these performance issues can be made more important when we take into account data locality.

Data locality and your cache

First of all, I debated with myself if I should talk about this. I concluded I shouldn’t, but programmers may riot if they read this and I didn’t mention it. So here we are.

So, data locality has to deal with the memory system of your computer once again. Recall how the computer moves things from RAM to cache to work on them? So well, turns out that movement is slow. Once it has things in the cache, it can work fast on them, but moving them may not be efficient. To deal with this engineers came up with a really smart solution; not move just the small part of memory you are working in RAM, but rather take a big window surrounding that. Turns out the trip from RAM to cache is not slower when doing this.

There are a lot of structures that can take advantage of this, and object pooling is one. Since you can put objects of the same type together on the objects pooler, they will be brought together into the cache when working on them. So, for example, if you got a bullet manager modifying your bullets, it can work on a big chunk of bullets at once instead of moving them one by one to the Cache and wasting time. The cache can be 100 times faster than RAM. Now you do the number on how much time the object pooler is saving you.

Concluding notes

As I hope I might have convinced you, using an object pooler has a lot of advantages for memory management and performance. It might not be the pattern to use for objects that are not destroyed (UI? The player? again depends on your game), but I really believe every game has some object pooler. Learn to be comfortable with them and use them!

Now, as I said before, I am oversimplifying the subject of this post. A pattern as important as this one cannot end here. There are different flavours of object pooling. If I were more precise with the Cache I could talk (write?) about object pooling with hot/cold split (or active/inactive split if you prefer that name), which is one I normally use. Maybe the subject of another post.

Edit: Not long ago I learnt that Godot actually does an object pooler for you when accesing objects from GDScripts. I guess in that particular edge case, this post be slightly less relevant.