What is a randomized game!?

Overview

For the past seven months, I have been developing a mod for Hades to be able to play it in a multiworld randomizer; Archipelago and it has been a really fun and interesting experience! However, if you are a normal person, the past sentence means nothing to you. What is a randomiser? what is a multiworld? Why is it called Archipelago? In this post I plan to answer two of those questions, so in a follow up I can roughly explain how to get a game into Archipelago and what problems I run while working on Hades.

Randomizers

First, I will start by explaining what is a randomizer. For this, I will first do a really simple example of how progression works on games, and how we can make a randomized experience out of it.

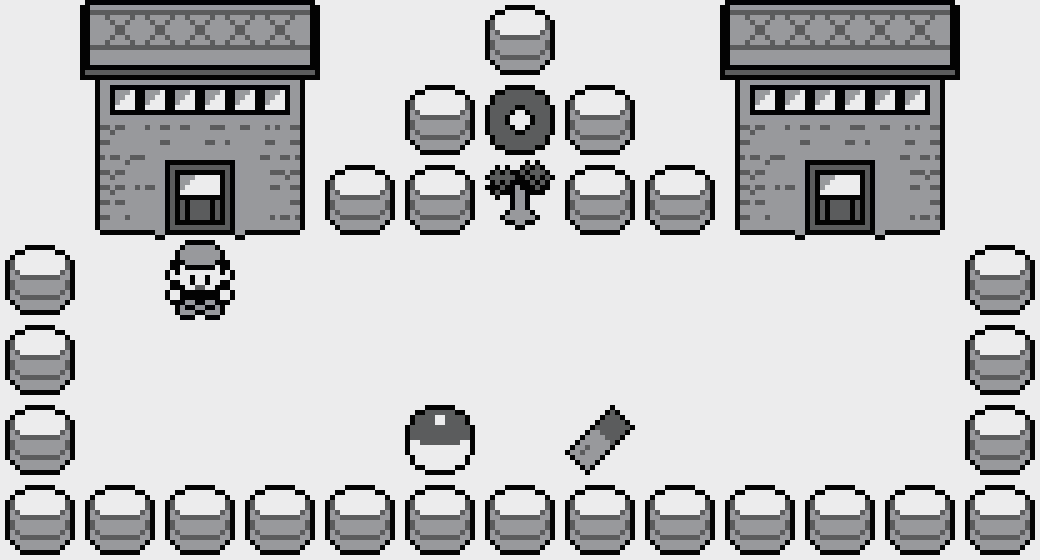

Imagine you are playing your favourite game, MonPoke. The progression of the game on the first town is to start choosing a MonPoke between 3, then to obtain an item that is not important (a Potion, let’s say), then to obtain a special ability (let’s say, cut) and use that to cut a tree to obtain an item (let’s say, a train pass) to exit the town.

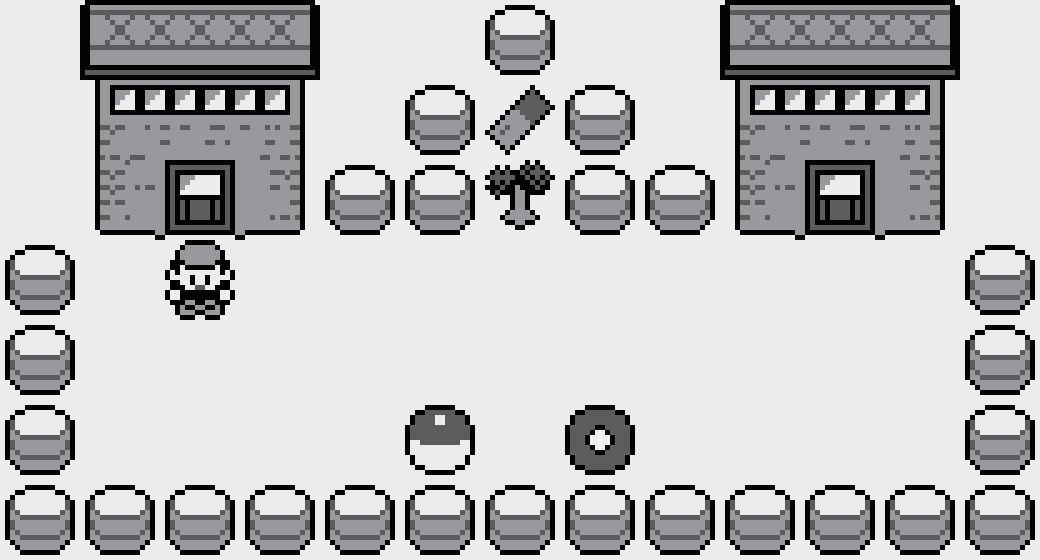

Potion is the sphere, cut the disc and the train pass is the piece of paper behind the tree. The sprites might be inspired by other game.

However, in a parallel world, cut is in the position of the potion and the game progresses regardless.

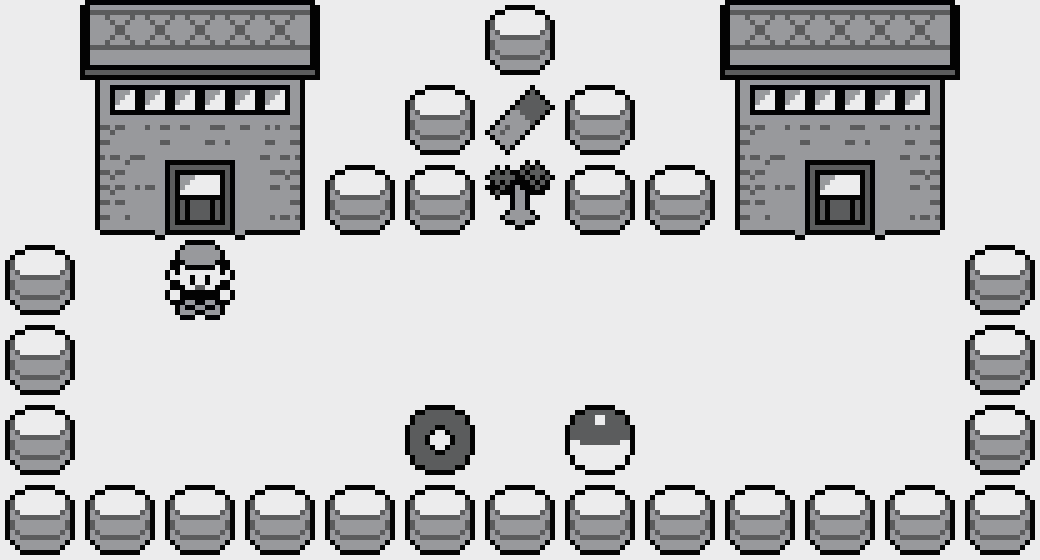

In a third parallel world, cut is behind the tree. Making cut impossible to get! However, we can still progress in the game, as we can get the train pass from another place in the game. But we are left without cut, most likely the game won’t be beatable that way!

Randomizers are the idea of actually implementing tools to simulate games from those “parallel” worlds as I called them before. To explain this concept I will introduce some terminology that is common to randomizers.

In what follows, we will refer to location as a place where an item could be. In our example, there are 3 locations, where the potion normally is, where cut normally is and where the train pass normally is. Note that locations are not necessarily places. Getting a reward from levelling up is also a location (even if it has no “physical place” in the game). We call the action of getting the item behind a particular location “checking the location”.

An item is whatever the player can obtain from some location in the game. In our example, that is the potion, cut and the train pass.

With this, we can explain what a randomiser is: a randomiser is a modification (commonly referred to as mod) of a game such that it changes (randomly) which item is found in which location. Note that the mod needs to make a decoupling; it needs to split the item from the location it is obtained. Only after this is done, it can shuffle the items and “reposition” them on location. That repositioning is done randomly. Note that, a computer cannot generate “true” randomness, and instead uses a number that is “basically random” (for example, the time in miliseconds of your pc) to generate “random-like numbers” . The number used to generate the randomness is called “seed”, and because of this reason, we abuse a bit notation and call “seed” all the particular randomness of an instance of a randomized game.

Note, however, in that definition we are not constraining ourselves to cases where the game is beatable. As shown in our third example, it could be that we leave cut behind a tree, making it impossible to obtain (and most likely blocking the game at some point). Is because of this, that we might want to include some checks to ensure the randomizer gives us a beatable game. We call Logic the series of rules given to a randomizer that ensures it will give us a beatable game.

As a final point of this section … WHY? Why would anyone want this? There are a couple of reasons, but I will speak for my experience. Randomizers change games you have played and loved so they feel fresh. It stops you from “autopiloting” the game because you can’t know it by heart (since it is randomized!). It is also a really fun experience! Same as games :P

Multiworld randomizer

Now you know what randomizers I can explain what a multi-world randomizer is. The base concept is the same, but in this case, we do not randomise the items of only one game … but several games and mix the items between them! Let me explain a bit how that works in theory.

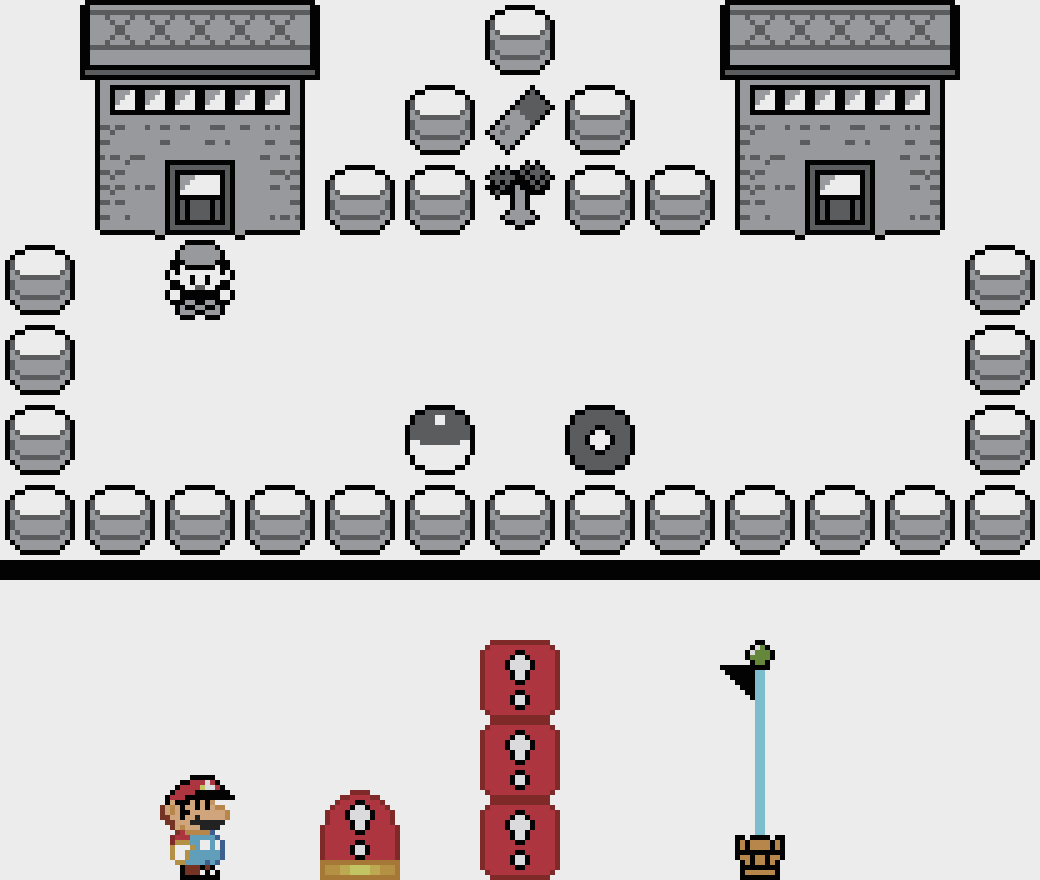

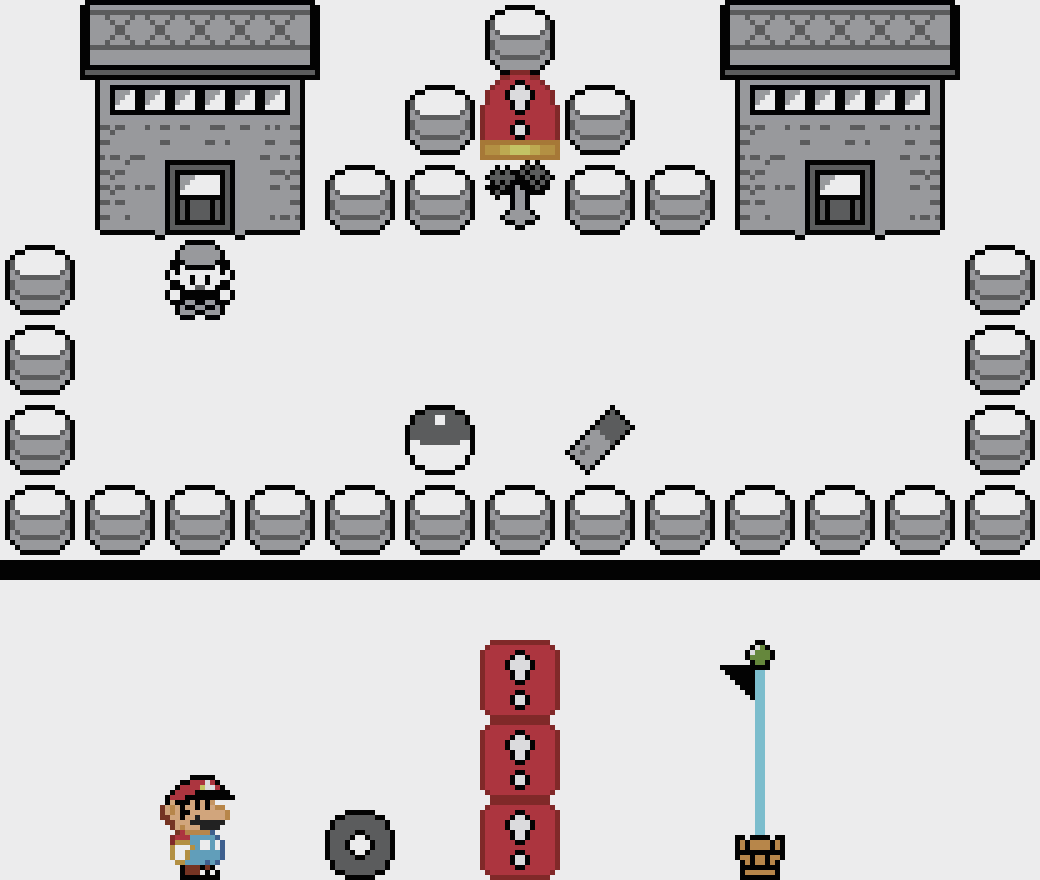

Imagine you are with a friend, and you are playing MonPoke and he is playing RioMa, you would both start in levels similar to this:

In this case, you progress in MonPoke same as we explained above and your friend just needs to press the red switch in RioMa to erase the red blocks, and then touch the flag to finish the level. However, we could randomise the items in both games to obtain something like this:

The situation changed. The MonPoke player can grab their train pass and go to the next town. However, the RioMa player needs the MonPoke to grab the red switch to open its way to the end of the level. In turn, the MonPoke player needs the RioMa player grab cut, to get to the red switch. There is now cooperation needed between both players to continue with their respective games.

Now this is exactly how a multiworld randomizer works! We randomized items between both games in a way that players need to cooperate. The idea is for both players to win their games.

How does that work?

There is more than one way this could work; but I will explain how it works in a particular case: the Archipelago multi-world randomizer.

In this case, we are going to have a server to send and receive items from the randomized game. A server is just a program that waits for a request and can answer back with some information. Normally these requests are sent through the Internet. In the case of Archipelago, the idea is to use a server to tell the games involved which items are placed in which location on the map. So when a game gets a location, it sends a request to the server saying “Hey, please give the item that was in this place”. In turn, the server reacts to these requests by sending the information required to the game saying “Hey, a player just unlocked this item for you”. In the example above, when the RioMa player grabs cut, the information that is sent to the server is “Hey, I grabbed the item in this location”. The server reacts by checking the information it has stored, notices the item in that location is cut from the MonPoke player and sends a message to the MonPoke player saying “Hey, the RioMa player sent you cut”. The game of MonPoke should then react and unlock cut to the player.

Note we added a new level of complexity to what the game needs to do. It needs to be able to interpret and correctly parse the messages from the server and modify the game accordingly. It should also be able to interpret what is to check a location and send that action to the server. This can be done in a game or an external program that runs this information and communicates tightly with the game (normally outside of the game not due to choice, but technical constraints). Whatever code routine that does this is called the client.

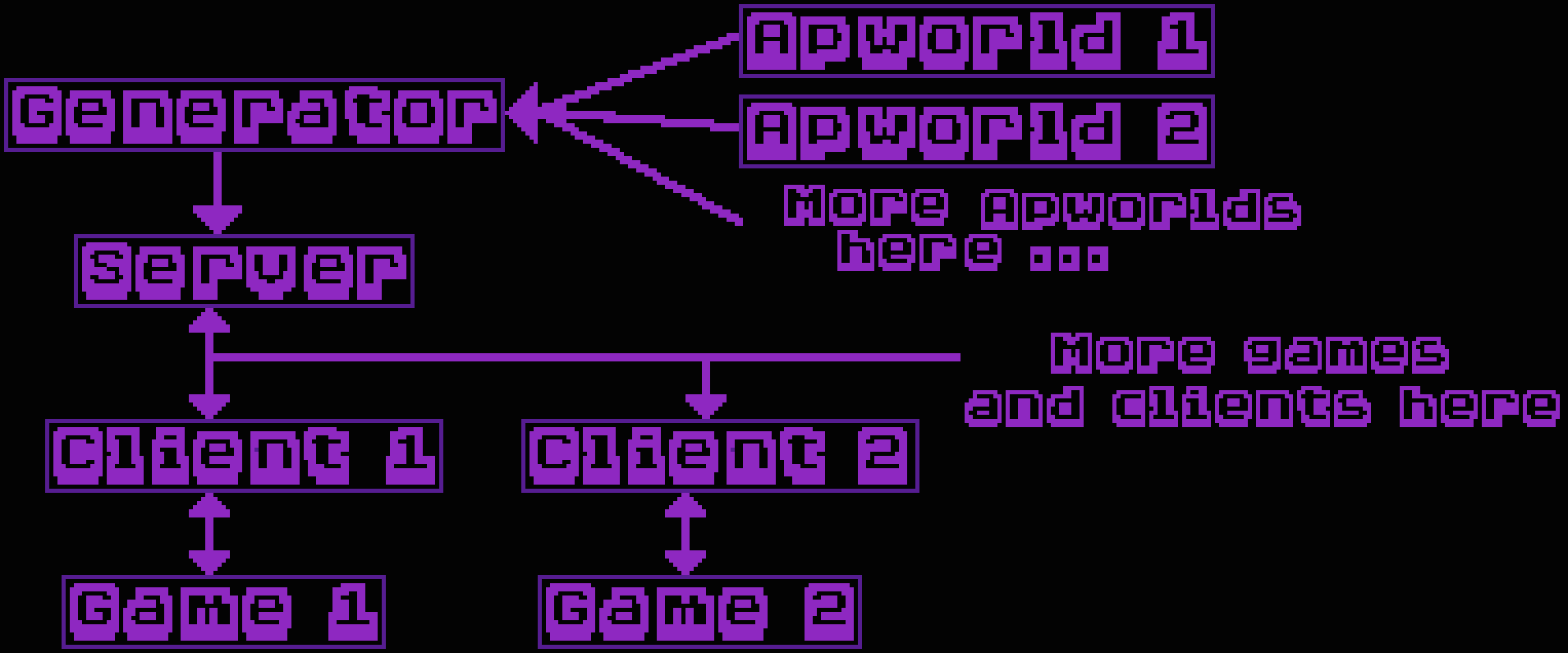

Now, one last question from all of this that went unanswered; how did the server get that information? Well, we give it to them. Before starting a game we do a generation process, not different to the one we do on a standard randomizer. However, the randomizer now must supply some information about each game, so that it can be randomized and ALL games are still beatable (remember we need some logic!). To do this, we give the generator a set of items, locations and the logic of the game. In the case of the Archipelago multiworld; that is contained in a .apworld file (which is just a bunch of Python files that codify the structure of the game). Furthermore, you can customize the logic of your game to adjust for difficulty or taste. This is done on a .yaml file, which the generator reads to adjust the options of the .apworld.

To finish, we can summarize all the information from this section in the following diagram!

Diagram of the different programs of the Archipelago. Arrows represent where information is sent.

I hope this explains a bit about how multi-world randomizers work. Now; interested in bringing your favourite game into Archipelago? Then check the next entry in which I detail how I did this for Hades. Hopefully you will learn a thing or two.